A note on the term ‘Queer’ - Part 2

In Mark’s introduction “A note on the term ‘Queer”, he discussed the reclamation of the word queer and it’s modern day usage.

In this entry, guest blogger and Conditions studio artist Kate Paul introduces us to queer theory and it’s use in academia.

You can find Kate and her work on Instagram.

(Some of the texts mentioned in this blog are available from Croydon Libraries which can be now accessed by the Select and Collect Service.

To find out more please click here)

As a child, I can remember the sense of turning my head away from the bodies of my teachers, who were always women; I turned my head away because I was too compelled to look.

Section 28, which was a law banning the ‘promoting’ of homosexuality as a ‘pretended family relationship’ in schools, was finally repealed in September 2003. I went to primary school in 1995. For the most part, ‘promoting’ meant to mention at all. This means that admitting the existence of homosexuality, in itself, was considered persuasion enough to draw children away from the traditional (real!) model of the heterosexual family.

From the childhood perspective of unspoken bodily experiences, ‘sexuality’ seemed to be about something allusive, something textural, something about misdirection ~looking away~ as much as direction or ‘orientation’. I spent years in internal resistance to the possible categories to describe these experiences, and seemingly to describe me, in my totality. When I later came across queer theories - which came to academic prominence at around the same time as I was trying to explain away my apparently unreal and anti-social desires - they made intuitive sense.

Largely, queer theories are analytical approaches which work to question the assumptions on which popular and academic understandings of sexuality and gender are based. They are used across different academic disciplines and are formed and influenced in relation to queer activisms. Queer theories are anti-simplistic, and often about holding contradictions together rather than creating binaries of thinking, for example, deciding between gay/straight, real/fake, male/female. Queer theory is different from related theories, like those within the field of Gay and Lesbian studies, because it questions categories rather than taking them as bases for fights for rights.

‘Queer Theory’, as a branch of academic enquiry, is generally dated back to 1990, to the eminent academic Teresa de Lauretis’s conference of the same name at The University of California, Santa Cruz. However, the term ‘queer theory’ was used by several theorists before then, for example Gloria Andaldúa, an influential writer and theorist of Chicana Studies. Queer, A Graphic History, by the writer and psychotherapist Meg John Barker and the illustrator Julia Scheele, notes several important antecedents to Queer Theory as an academic field.

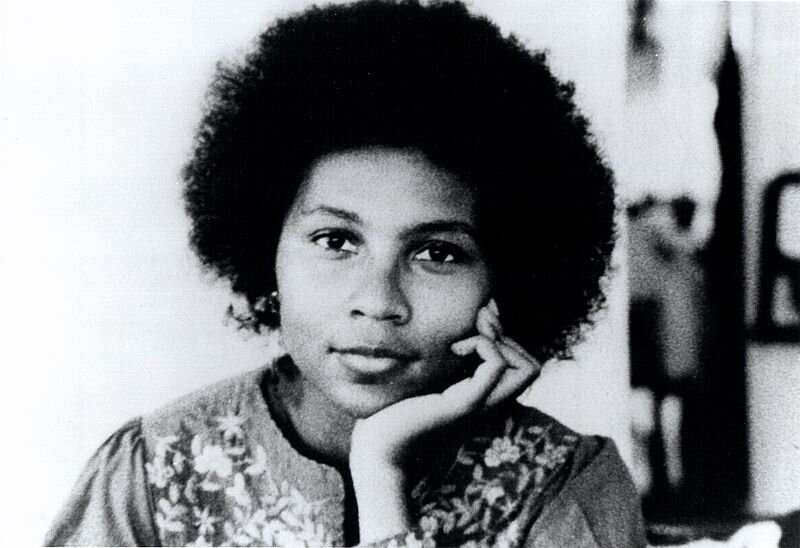

For example, Barker highlights the importance of Black feminist thinking in the 80s by writers and theorists like Audre Lorde and bell hooks, which allowed for questioning of the term ‘woman’ as an identity category. If the experience of a Black woman is so different to that of a white woman, then on what basis is the category ‘woman’ an important one to uphold? This work can be linked to the work of Gender Trouble (1990), an influential queer theoretical text by the philosopher and academic Judith Butler, which considers gender not as something that we categorically are, but as something that we are continually doing.

‘Queer Theory’, as a branch of academic enquiry, is generally dated back to 1990, to the eminent academic Teresa de Lauretis’s conference of the same name at The University of California, Santa Cruz. However, the term ‘queer theory’ was used by several theorists before then, for example Gloria Andaldúa, an influential writer and theorist of Chicana Studies. Queer, A Graphic History, by the writer and psychotherapist Meg John Barker and the illustrator Julia Scheele, notes several important antecedents to Queer Theory as an academic field.

For example, Barker highlights the importance of Black feminist thinking in the 80s by writers and theorists like Audre Lorde and bell hooks, which allowed for questioning of the term ‘woman’ as an identity category. If the experience of a Black woman is so different to that of a white woman, then on what basis is the category ‘woman’ an important one to uphold? This work can be linked to the work of Gender Trouble (1990), an influential queer theoretical text by the philosopher and academic Judith Butler, which considers gender not as something that we categorically are, but as something that we are continually doing.

Barker also notes shifts in queer activisms in light of the Aids crisis of the 80s and 90s, away from struggles for assimilation into traditional family models, and towards struggles for liberation. This moment in the formation of queer theories, when thinking shifted as a result of mass sickness and disability in queer communities, can be linked to a related way of thinking, Crip Theory, which is largely about challenging assumptions and categorisations related to dis/ability and the body.

by Kate Paul, Artist

Some of the texts mentioned in this blog are available from Croydon Libraries which can be now accessed by the Select and Collect Service.

To find out more please click here

References:

Queer: A Graphic History by Meg John Barker and Julia Scheele (available at Croydon Library)

Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism by bell hooks (available at Croydon Library)

Queer Magic: LGBT+ Culture and Spirituality from Around the World by Tomas Prower (available at Croydon Library)

Examined Life with Sunaura Taylor and Judith Butler https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R_N84BffPcM

Crip Theory by Robert McRuer

Gender Trouble by Judith Butler

Queer Phenomenology by Sara Ahmed