Queer Symbols

Guest blogger, Clara Atkinson discusses queer symbols and the importance of their visibility in the LGBT+ community.

Clara is an artist with a BA from the Ruskin School of Art. She is currently part of Conditions Studio Programme in Croydon. Her work looks at language, technology, symbols and material histories. View her Instagram here

San Francisco, Pink Triangle.

Image: Christopher Michel, Flickr

What signs and symbols do we use to navigate through the world? Where do they come from and how do their meanings change through use? In my work, I am interested in the way in which symbols are used within the context of queer histories and identities.

A common experience of navigating the world as a queer person is being very aware of symbols — intrinsic to queer identities are the ways in which these identities are expressed, whether through language or through images, clothing and behaviour. Often, certain symbols are used as code or visual shorthand, popping up “like a wink” to denote the presence of a shared community and to mark the boundaries of spaces.

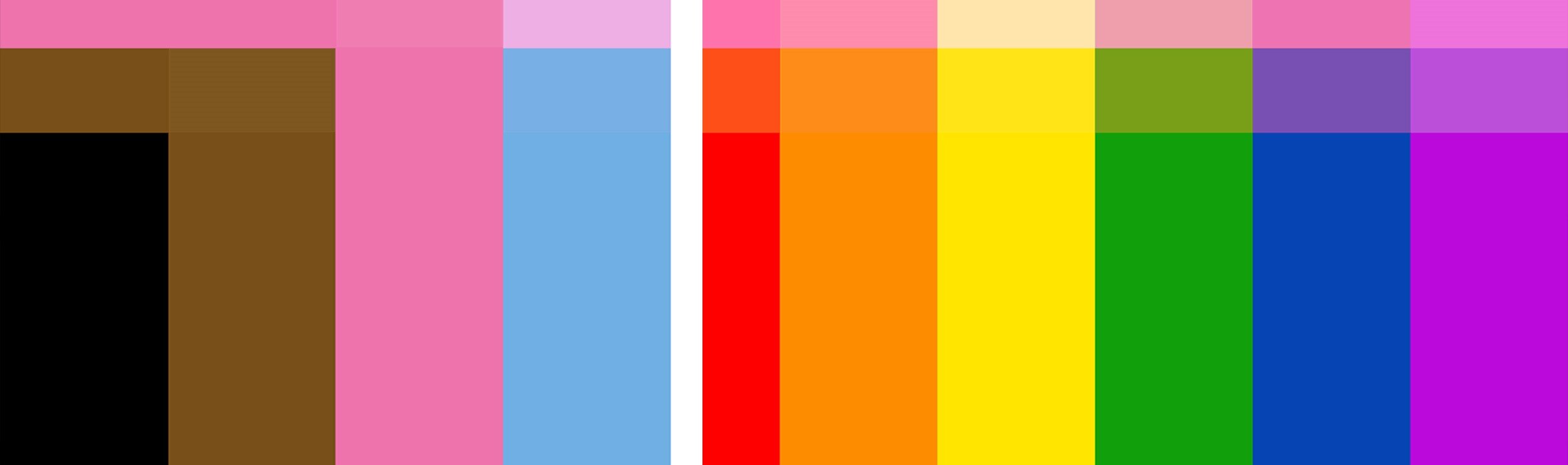

One of the most universally recognisable of these is the rainbow flag. Since its creation in 1978 by Gilbert Baker, it has become increasingly familiar — especially during pride month, when everyone from Coca-Cola to the Met Police can be seen in its colours. This co-option of the flag by capitalist consumption can make it easy to dismiss as an effective symbol of queer liberation. However, this would bypass the importance that the rainbow can hold in people’s day-to-day lives, especially in environments that are not otherwise queer-friendly. For example, a recent study found that, for a large number of queer youth living in rural areas, the rainbow flag represented affirmation, “safety and support”. As much as they were aware of its limitations, the symbol allowed them to construct and share meaning, and to connect with a community (whether present and real, or future and imagined).

Modern day Gay Pride flag

Image: Hanna Sörensson, Flickr

Baker’s aim was to create a symbol that would universally appeal and unify. Borrowing from the civil rights and hippie movements, the flag’s imagery is elementary. ‘It’s a natural flag’ Baker said, ‘from the sky’. However, this design is double-edged, as its insistence on naturalistic neutrality can leave it devoid of politics, broad but not deep.

In contrast, the pink triangle is grounded in a highly specific historical and political context. First used in Nazi concentration camps to identify homosexual men, it was reclaimed by activists during the AIDS crisis as a powerful symbol for the death of queer bodies at the hands of institutional homophobia. ACT-UP alluded to this history in their manifesto, where they wrote that ‘silence about the oppression of gay people, then and now, must be broken’. In contrast to the rainbow’s sunny optimism, remembering is central to the symbolism of the pink triangle. It’s a symbol of collective memory and meaning, of the friction and difficulties of queer lives, both then and now.

But it’s not all about loss and mourning. There’s definitely room for joy and defiance in the symbol, as it’s adopted and worn by people all over the world. But maybe it’s a more complex joy — an acknowledgement that our histories (and lives) are multilayered. The pink triangle can be aligned with theorist Sarah Ahmed’s notion of “queer happiness” as being a choice which rejects triumphalist narratives, moving “beyond the straight lines of happiness scripts” (Sarah Ahmed, The Promise of Happiness) and rejecting a depoliticised gay culture in favour of a closer relationship to history, trauma, conflict and desire.

Symbols tie us into a collective memory — located not just in the archive, but in the living surfaces of the world, where the past is brought into and transformed by the context of the present. They form a web of connections, associations and shared experience, producing cartographies of communication and touch-points for communities. And their meanings are plastic; they are made and re-made through use and time.

by Clara Atkinson, Artist

Sources

Chasing the rainbow: lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer youth and pride semiotics